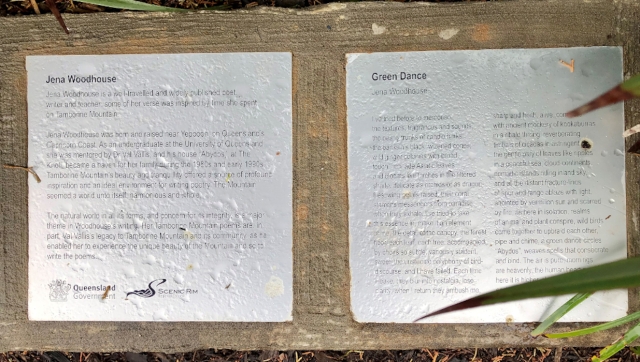

Featured image Jena Woodhouse poetry sculpture (lines from ‘Green Dance’) in Main Street, Tamborine Mountain

A sense of anticipation stirs. I sit with a large archive box marked ‘Vallis’ at a wide wooden desk in the University of Queensland’s Fryer Library. Other boxes await. I lift the box’s lid.

Valentine Vallis (known as ‘Val’) died in 2009. Poet, scholar, returned World War II soldier, opera enthusiast. Literature academic at UQ for much of his career. And … sometimes-sojourner on Tamborine Mountain. Where I live.

By all reports, Val stopped writing poems long before he bought his neat weatherboard week-ender on Knoll Road at the northern end of the Mountain. I’m sceptical. Surely Val’s creative impulses had been revived in – by – the rainforest? Hence my trip.

Novelist Gail Jones confesses she’s a literary nerd who likes ferreting around the places associated with her favourite authors. ‘I’m interested in the trace they leave,’ she says.1 I know where Jones is coming from. In my mid-20s, on my first visit to the UK, my bible was The Oxford Guide to Literary Britain and Ireland rather than Europe on $20 a Day.

My search is the reverse of such literary pilgrimages. I’m starting with the place where I live and which I love, and hunting for its literature.

Luckily, Val’s papers are neatly sorted and labelled. The search is slow. Lengthy correspondence. Teaching notes, opera reviews, newspaper cuttings, letters.

My heart skips. Poems. Typed, on individual sheets; unsigned, no name. I quickly thumb through the box. Six of them: ‘Cicadas’, ‘Mountain Song’, ‘Currawongs and Magpies’, ‘Night on the Mountain’, ‘Green Dance’ and ‘Wood Stove’ – “Abydos”’ (the name of Val’s Mountain house).

Eureka.

* * *

For three years, a group of people has been ‘doing poetry’ on Tamborine Mountain. For me, this started with writing a play, ‘Hearts Ablaze’, based on Judith Wright’s letters and poems, to celebrate the 2015 centenary of her birth, and the 30 years she spent on the Mountain.

Doing theatre bonds people, but they scatter once the production is over. In this case, infused by the joyous energy of Judith’s work, we continue to meet. Poetry readings in the local pub, Clancy’s, become a regular gig, and sell out. Ambitiously, we hold a mini poetry festival in 2016. In 2017 we publish work by local poet Raymond Curtis.2 We form a book circle to read the difficult philosophical work of Jack McKinney (Judith’s partner).

The idea is to ‘do poetry’ in the streets and the rainforests. ‘The street’ is often Main Street (literally, the locals’ main street), which becomes Knoll Road at its northern end. We call ourselves the Calanthe Collective, after the house Judith and Jack owned on Long Road.

These events are a little random, but they’re fun.

Importantly, people write poetry, and share it.

The poetry bug has bitten me late in life, but it has bitten hard. I have found a ‘tribe’ that connects to place and to people I come to know and like a great deal.

Now here I am in Fryer Library, my white-gloved hands cautiously grasping at this new-found treasure.

* * *

As I collect another box, eager for more poems, I blurt out to the librarian, ‘I’ve found the lost Tamborine Mountain poems of Val Vallis’. My search may never have happened without the encouragement of Fryer librarian Joan Keating. But Joan’s not here today. Recognising my emotion, but not knowing the story, the librarian on duty gives me a warm, albeit puzzled, smile.

Before I open the next box, I re-read the six poems more carefully. No mistaking where they were written. As a regular walker along Knoll Rd, I recognise these very

fronds

that cartwheel into sky, slim-columned

palms, and huge green hands of giant

stinging-trees.

But elation gives way to confusion, and slight embarrassment, given my recent effusion. Val – a poet of the water, the shoreline, netmakers and fishing people, the Capricorn coast – wrote poems altogether different in language and structure from the rainforest web woven here.3 Lovely poems, but not Val’s. Whose?

The next box is full of Val’s diaries, which look like mine. No reflections, no thoughts, just brief notes of appointments, lunches, meetings, bookings.

A gear in my brain clicks. Bookings, indeed, for the house on Knoll Road. Brisbane-based, Val lived there only intermittently, but he was a warm host in absentia, judging by the number of people who stayed.

I note the names of regular guests. Enquiries follow: of Fryer librarians, of AustLit, of literature academics, of a Gladstone poet who was Val’s friend, of Val’s family. An email trail takes less than a week to find Jena Woodhouse.

* * *

Eight months after my day in Fryer Library, Jena and I sit outside a café in Main Street, sipping coffee. The morning sun slants down, silvering the fronds of newly-planted piccabeen palms on the median strip, and warming the early morning caffeine addicts.

Jena is sweet-faced, smooth-skinned, her red hair pulled back by a peach-coloured, silver-spangled scarf. She’s led a somewhat gypsy life, with long sojourns in Greece and writers’ residencies all over. Always writing: short stories, novels, hundreds of published poems, earning a living by editing, teaching, English language examining. She tells me the story of a lost mother goat, lamenting her dead kid in a cave above a rocky shore on the Greek island of Kos. And many other tales, with the keen recall and even keener eye of the poet.

Memories of Tamborine thirty years ago soon tumble out. Jena was first Val’s student, and later his friend, often-sojourner at Abydos in the late ‘80s thanks to his generosity. Jena speaks of the house as ‘a unique sanctum, [its] significance not tarnished by time’. She adds:

The key to ‘Abydos’ was my passport to those vital connections between spirit and place that are the essence of much of my writing: an incalculable gift.

Twelve of Jena’s Tamborine Mountain poems are in a folder in my bag, six from Val’s boxes, and six others – published in various journals – which Jena has found for me. Calanthe will soon publish a slim book of these ‘lost poems found’.

Already one of Jena’s poems has taken root in the soil from which the verses originated. Scenic Rim Regional Council has engaged a landscape architect to consult with the community, to design a new median strip for Main Street. The process is not without controversy; a handful of locals raise voices against the ‘desecration of heritage’.4 None but they see the ‘heritage’ value in dying grass and broken benches. Heritage is what’s best about the natural and human world, surely? Poetry is part of our heritage.

Thankfully Council – via the Mountain’s two local councillors and council’s Cultural Services department – is sympathetic to the literary heritage of the Mountain.

The median strip work is finished by March 2018. Amongst new plantings, seating, shelter sheds, low walls and paths, are four poetry installations, by different authors, in curving arcs of reddish weathered Corten steel, echoing the red soil. Rather monumental, containing a stanza or two of poetry, with the full poem set out in a nearby plaque. They catch the eye, without dominating the space.

Besides Jena’s, there is work by Judith Wright, 90-year-old Raymond Curtis, and Wangerriburra elder Aunty Ruby Sims. Historical signboards record the efforts of ‘rainforest women’, local naturalists and botanists who have been, for 150 years, guardians of the environment, many authors themselves.5 And before that, the long-term custodians, Aunty Ruby’s people.

Council invited The Calanthe Collective to select the poetry. So… we long-listed, then short-listed, then voted on the poems. In August 2017, I email Jena:

Today I read ‘Morning Walk at Tamborine’ to the council works officer (and the local councillor) as we did a ‘site visit’ to discuss location of the poetry installations; first time he’d been read poetry by a ratepayer, he said.

‘Morning Walk’ was on Calanthe’s long list, but the last four lines of Jena’s ‘Green Dance’ are chosen and installed on Main Street. This breathless poem, a single stanza so that the rhythm, the ‘green dance [that] circles Abydos’, is smooth and uninterrupted, finishes:

The air is pure, mornings

are heavenly, the human heart goes free;

here it is higher, clearer, lighter,

easier to breathe.

I imagine walkers along the median strip stopping, noticing, reading the full poem, perhaps recalling

all the distant fracture-lines

of spur and range ablaze with light

as they gaze westward at sunset. Or, as they hike the national parks, seeing with fresh eyes

wild ginger colonies with broad,

tough, rich jade Asiatic leaves

and blooms like torches in the filtered

shade … .

The Calanthe Collective has sought to put poetry in the streets of Tamborine Mountain; the poetry sculptures are the latest (and most literal) step in that process. The night before the Main Street opening, Calanthe proclaims Tamborine Mountain ‘the poetry capital of Australia’, after a Guinness or three at Clancy’s and listening to Jena read her work. A cheeky claim, but why not?

* * *

Main Street, an unassuming precinct, is now a tangible literary place; newly-minted, but a microcosm of the hidden literary trails criss-crossing the Mountain. These paths overlap in space and occasionally in time.

Jena’s trail naturally follows Knoll Road, in the late 80s and early 90s, as she walks to Knoll National Park with her young son and his friend – ‘to tire them out’ – in the morning, and to the pizza shop in Main Street in the evening. Each day, she spends several hours composing poems at the corner window of ‘Abydos’, looking north-east through the rainforest to the coast.

Raymond Curtis’s trail goes all over. He is not a sojourner but rather a dweller, for most of his 90 years. An exquisite childhood memoir records his 1930s childhood, and a year-long diary in the tradition of Annie Dillard’s Pilgrim at Tinker Creek his time as a park ranger.6 Always the meticulous observer; as in ‘Spider-craft’, on the median strip:

On the star-bright Earth they have laid their wares,

and now in the dawn we see

they have slung their glimmering gossamer gems

from every tussock and tree.

Leaning on his stick, Raymond’s walking range now is short. But his mind ranges far, and he writes poetry and stories in his graceful, looping longhand.

Judith Wright spent 30 years, from the mid-40s to the early 1970s, wandering the Tamborine plateau, from her tiny cottage ‘Quantum’ and then her house Calanthe on Long Road. She and her partner Jack McKinney tramped to the western lookouts and up Knoll Road several decades before Jena.

From Wright’s huge and important output,7 Main Street features ‘Song’, which starts:

O where does the dancer dance–

the invisible centre spin–

whose bright periphery holds

the world we wander in?

This secular hymn to the unknown and the unknowable, the imperfect and the impermanent, is a sharp counterpoint to the green, humid realities of Woodhouse’s work. Both, in different ways, invoke images of the dance.

Aunty Ruby has the biggest claim in terms of chronology. Tens of thousands of years of storytellers. She’s a Scenic Rim elder with strong descent lines via her mother to both the Mununjali people of the Beaudesert area and to the Wangerriburra people of Tamborine Mountain. Living in nearby Kooralbyn, Aunty Ruby increasingly ‘comes home’ up the winding roads to make connection with country again, and to make new friends. After a visit when for various reasons we fail to meet up as planned, she emails me:

It was rather funny in a sense but at least I did get to visit my Great Granny Lucy’s magical mountain home in the softness of the night drive with friendly trees bowing down to us along the way.

To the Main Street venture, Aunty Ruby contributes this:

Look after the Land

She is our Mother

Honour each person

As sister and brother

Honour the Elders

Share with each otherThen rain will come the Land to cover.

For me, out of these writings comes a sense of Tamborine Mountain ‘as a subjective experience, as something … lived emotionally and imaginatively in the private lives of people’s innermost thoughts’ as Tony Hughes-d’Aeth puts it in his marvellous literary history of WA’s wheatbelt.8 Ruth Blair, in her lovely piece about Wright, Curtis and a third Mountain poet, Mabel Forrest,9 first drew my attention to the Mountain’s interconnected layers of literary culture, showing how Tamborine writers respond to ‘the fluid borderlines’ between the wild and the cultivated, and to a place that has retained its beauty despite many depredations.

Like Sheahan-Bright, I believe there is ‘a rich vein to be mined into a community’s memory by delving into its creative writing’.10

The search hasn’t ended with Val’s boxes in Fryer.

* * *

The week before our café meeting Jena sends me a new poem, about the Richmond Birdwing butterfly. I ask her what it’s like to be back on the Mountain, as she’s made a few visits recently, and she responds:

The Knoll and the approach to it have altered little. The air seems to change as one enters Knoll Road. The thread of poetry has re-emerged in response to recent contact with the mountain’s essential identity, and holds it all together in the consciousness, irrespective of time and change and absences.

We finish our coffees, and head to the Historical Society’s Museum in Wongawallan Road. As we’re entering the gate, a yellow-tailed black cockatoo wheels and cries overhead.

Raymond Curtis is there, playing his grandparents’ piano, as he does every Tuesday morning. He and Jena duet with Scottish airs, hugging as they part. For once, at least, two literary trails cross, in time as well as space.

The next day, Jena sends me a poem about the cockatoo.

Postscript: Green Dance: Tamborine Mountain Poems by Jena Woodhouse, the first publication of Calanthe Press, was launched by Fryer Librarian Simon Farley in August 2018. It contains Jena’s original poems, plus others written when she reconnected with Tamborine Mountain in 2017. Obtainable by emailing Geoff Cartwright, calanthepress@gmail.com; RRP $18 plus $3.50 packaging and postage. Raymond Curtis died in December, 2018, and is buried near Judith Wright and Jack McKinney in the cemetery on Tamborine Mountain. He is much missed. His The View Westward is $20 plus $3.50. Further volumes are Anthony Lawrence (Time Machine, 2019), Jane Frank (Wide River, 2020) and Vanessa Page (Botanical Skin, 2021). A volume by Stuart Cooke (Land Art) is forthcoming in early 2022.

– Janis Bailey

References

1 C Baum, ‘Gail Jones: Novels are machines for feeling as well as thinking’, Sydney Morning Herald, 6 April 2018, viewed 6 April 2018, <https://www.smh.com.au/entertainment/books/gail-jones-novels-are-machines-for-thinking-as-well-as-feeling-20180328-h0y2hu.html>.

2 R Curtis, The view westward: Tamborine Mountain poems, Raymond Curtis, Tamborine Mountain, 2017.

3 V Vallis, Songs of the east coast, Angus and Robertson, Sydney, 1947. V Vallis, Dark wind blowing, Jacaranda Press, Brisbane, 1961.

4 J Wilkinson, ‘Tamborine Mountain divided by its Main St village green’, The Gold Coast Hinterlander, April 2018, p. 2.

5 For example, G Aagard, Wildlife in a wild garden: a Tamborine Mountain journal, Glyn Aagard, North Tamborine, 2000. See also: H Curtis ‘Hilda Curtis’, in J McKay (ed), Brilliant careers: women collectors and illustrators in Queensland, Queensland Museum, Brisbane, 1997; S Sewell Women and the environment: an indicative study on Tamborine Mountain, PhD thesis, James Cook University, 2014, viewed 13 April 2018, <https://researchonline.jcu.edu.au/35058/1/35058-sewell-2014-thesis.pdf>.

6 R Curtis, Bright morning: memories of childhood in the nineteen thirties on Tamborine Mountain, Raymond Curtis, Tamborine Mountain, 2014. R Curtis, Rainforest journal: Tamborine Mountain national parks 1980, Raymond Curtis, Tamborine Mountain, 2003.

7 J Wright, Judith Wright: collected poems 1942-1985, Fourth Estate, Sydney, 2016.

8 T Hughes-d’Aeth, Like nothing on this earth: a literary history of the Wheatbelt, UWA Publishing, Perth, 2018, p. 8.

9 R Blair, ‘Hugging the shore: the green mountains of South-East Queensland’, in CA Cranston and R Zeller (eds), The littoral zone: Australian contexts and their writers, Rodopi, Amsterdam, 2007, pp. 177-197, p. 193.

10 R Sheahan-Bright, Kookaburra shells: Port Curtis literature, Justified Press, Gladstone, 2006. More generally re literature and place in Queensland, see: P Buckridge & B McKay (eds) (2007) By the book: a literary history of Queensland, University of Queensland Press, Brisbane, 2007.

————————————————————–

Janis Bailey wrote Hearts Ablaze, a play about Judith Wright’s and Jack McKinney’s Tamborine Mountain years, in Judith’s birth centenary year (2015), and since then has been a poetry tragic. With friends, she founded Calanthe Collective in 2016, a grassroots community cultural initiative, based on Tamborine Mountain in south-east Queensland, fostering poetry (writing and performance) and allied arts. An offshoot of the Collective has been Calanthe Press, founded in 2018. This piece was written whilst a student of Dr Stephanie Green in her post-graduate Creative Non-fiction subject at Griffith University

Janis Bailey wrote Hearts Ablaze, a play about Judith Wright’s and Jack McKinney’s Tamborine Mountain years, in Judith’s birth centenary year (2015), and since then has been a poetry tragic. With friends, she founded Calanthe Collective in 2016, a grassroots community cultural initiative, based on Tamborine Mountain in south-east Queensland, fostering poetry (writing and performance) and allied arts. An offshoot of the Collective has been Calanthe Press, founded in 2018. This piece was written whilst a student of Dr Stephanie Green in her post-graduate Creative Non-fiction subject at Griffith University

..

. ————————————————————–