The Wild Swans at Fairhaven

Far out on the lake

the swans play their mournful flutes,

while the light goes

to wherever the light goes.

Far out on the now dark lake

the swans whine like hounds

while we lie here

in our kennel of lamplight.

The swans, the black swans, improvise

constellations of sweet and sour notes

in their cold, their night-hushed auditorium;

fall silent, then mourn a little more

while we lie half-listening,

half-feeling we’ve forgotten something –

maybe our other name

in our other life.

**

Dry spring

After two years absence,

the bellbirds are back,

thronging of an evening

to the big stone bowl

on the back deck;

half a dozen at a time

taking turns to plunge

each for a split second

beneath the turbid water

while the others look on,

congenially peeping.

Vivid, somewhat manic

small birds, the late sun ignites

their olive-green plumage,

the lifebelt orange bills

and claws by which they hold

to the nine railing wires

like notes on a stave –

except these notes

never stop moving; they’re

beyond the composer’s control.

Their music writes itself.

**

Ampersands

Sometimes it’s hard having

bulging ampersands

that hook you up to everything

so you can’t drop anything,

like in the hotel buffet becoming a walrus

(by walrus I mean something they

look at and say Nah, not human;

I don’t mean literally a fat seal with tusks).

So there you are, hooked on addition,

piling your plate with observations,

images, just one more simile, groaning,

hauling yourself up on to the pavlova

by your huge curved yellow teeth.

**

Ice cream

The last time we took my father out

it was just down the coast to Paekakariki

with its dingy beach cluttered by driftwood,

looking west to humped green Kapiti

and Te Wai Pounamu across the strait.

To my surprise there were cafes and gift shops,

clothes boutiques, an attempt

at a weekend shopping street:

New Zealand had changed in our absence.

Our objective was ice cream, a treat

after the nursing home’s industrial food.

We found it in on the beachfront,

in a homewares shop with a cold cabinet.

He could still walk a little unaided;

his long program of self-neglect hadn’t quite

confined him to the window-seat in his room,

listening all day to National Radio.

He had no truck with therapy,

saw no point in chewing the fat.

But it was hard to watch someone slowly

closing the shutters on himself. So, ice cream

in a small paper dish, with a sea view;

that New Zealand chill even in summer

keeping us indoors as we meditatively spooned.

It was then he made Rajni a gift,

after she showed it to us, said she liked it:

the egg timer in the shape of a hen

which still sits on our kitchen windowsill,

its spring long ago loosened to uselessness.

**

Wave

Over your shoulder,

through the salt-grimed window

of the Bulli Beach Café,

I see a wave break perfectly.

It’s come a long way, maybe from Chile,

to break just for me—well,

chances are, I’m the only one

watching this particular wave

curl, break crisply, steadily

blue-green into white

down 100 metres of tube.

It cries out for a surfer,

but all the surfers have gone home:

they’re watching TV, cracking

the second beer – and it’s only me

over the rim of my own glass

who watch this wave, its pure demise.

That’s how it is to be

a so-so poet on the South Coast:

you feel responsible for each wave,

as it does its best, cuts its dash,

spreads the sand with lace

and makes your heart ache

with its pointless panache.

**

Beachcomber

I’m making a poem

out of things I found on the beach:

a bit of driftwood, a shell,

a gull’s feather still dusted with sand.

I arrange them in short lines,

not too many (it’s 2025;

readers are short of time),

fasten them lightly with commas,

weave dune-grass for string.

You know how it is with beachcombings:

for a while they seem to bring

the sea’s lustre, salt and ozone

back with them, into your home,

until they fade.

Writing such a poem as a young man,

I’d feel powerful, but four decades on,

it’s the weakness I notice.

So I use that for fixative

to seal my assemblage

with a hint of the horizon,

that uncanny blue-grey light;

the shell still whispering secrets

our ears can’t quite decipher.

What do you think?

It’s the quality of failure, don’t you find,

that makes a poem, for a little while

stand, fragile, until time,

like the smallest wave,

brushes it away.

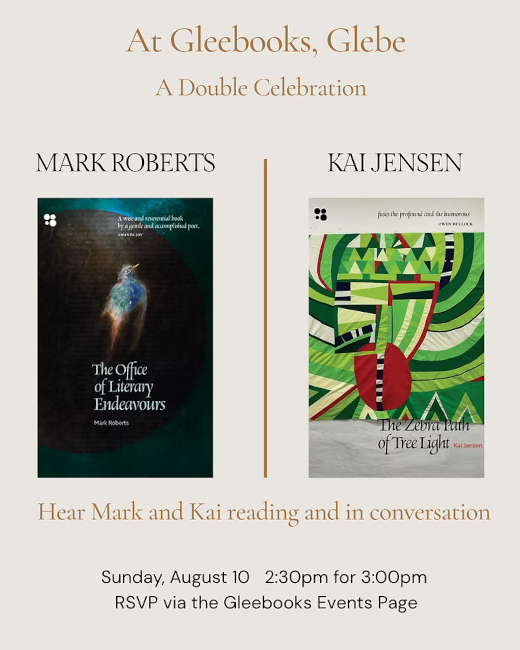

Kai Jensen was born in Philadelphia, USA; he lived from the age of five in Aotearoa/New Zealand, then moved to Australia with his Australian wife Rajni (Kathy) Troup in 2004, and is now learning to be Australian. Kai’s poems have appeared in most leading Australasian literary journals, and in many North American journals; his first book of poetry, The Zebra Path of Tree Light, was published by 5 Islands Press in May 2025.