In November 2023, I had the privilege of speaking at Bodies of Work – A Symposium, held at Vitalstatistix in Adelaide, organised by Emma Webb, Justin O’Connor and Tully Barnett. Centred on the theme of “Labour rights for artists, cultural democracy for workers”, a significant portion of the conference was dedicated to examining the Australia Council’s Art and Working Life program of the 1980s as well as current arts policy.

However, the highlight presentation for me came from two Irish speakers who were instrumental in establishing a basic income trial for artists in their home country: Angela Dorgan, CEO of First Music Contact and former Chair of National Campaign for the Arts who championed the Basic Income for Artists pilot in Ireland; and Sharon Barry, Director, Culture Ireland.

This pioneering trial provided a supporting wage for several years to an anonymous group of 2,000 artists randomly selected from a pool of applicants, with their outcomes benchmarked against an equivalent anonymous and randomly selected control group. The recently published results of this research have been nothing short of spectacular, demonstrating the profound success of the initiative. The Irish government has now made the program a permanent fixture, a testament to its efficacy.

For many years, I have been a vocal proponent of a universal basic income (UBI) for everyone in Australia but I have (only partly jokingly) described it as a Universal Art Grant and the best possible solution to arts funding. My persistent advocacy has often been met with weary resignation from figures like Tony Burke, who has come to expect my regular appeals for a shift in our arts funding paradigm. My position has always been that the most effective way to support the arts is to provide artists with the time and financial stability to create, completely free from the constraints of project-based applications and acquittals. The Irish experiment provides a powerful and compelling validation of this approach.

The current system of project funding, with its endless applications and peer assessments, has over time degenerated into a bankrupt model that fails to consistently deliver meaningful results. The success of the Irish program, which is now being replicated in other forms, suggests that even a system of sortition, or random allocation of grants to a broad pool of applicants, could yield equally, if not more, favourable outcomes.

I have compiled this research paper that delves into the history of the Irish basic income for artists trial program. It is my hope that by examining this successful model, we can inspire a much-needed conversation about the future of arts funding in Australia and move towards a system that truly effectively supports artists rather than controls and polices some of them while failing the vast majority by ignoring or excluding them.

Statement of interest: Even though I have at times worked in various capacities for the Australia Council, and even brokered funding for others, I have never received a personal grant from them. For decades they had no category for me then later when they caught up with reality a bit I was still consistently rejected until eventually I gave up. I would argue this makes me a completely objective commentator, uncorrupted by their money. LOL.

Ireland’s Pioneering Basic Income for the Arts

1. Executive Summary

This report provides a comprehensive analysis of Ireland’s Basic Income for the Arts (BIA) scheme, a groundbreaking initiative that has garnered significant international attention. This research confirms that Ireland has not only introduced but is now making permanent a form of basic income for artists. The pilot program, launched in 2022, has been deemed a success, leading to its inclusion as a permanent program in the 2026 budget. The scheme provides a weekly payment of €325 to 2,000 artists and creative workers, with plans for expansion. This report details the program’s structure, its economic and social impacts, the political context surrounding its implementation, and its place within a global movement for guaranteed income for creative professionals.

2. Introduction

The concept of a basic income, a regular and unconditional payment to individuals, has been a subject of debate for decades. In recent years, a specific application of this idea has gained traction: a basic income for artists. This approach seeks to address the financial precarity and unpredictable working conditions that are endemic to the creative sector. Ireland has emerged as a global leader in this policy area with its Basic Income for the Arts (BIA) scheme. This report offers a deep dive into the BIA, examining its origins, implementation, and impacts.

3. Ireland’s Basic Income for the Arts (BIA) Scheme

3.1. Program Overview

The BIA scheme is a landmark policy initiative administered by the Irish government’s Department of Tourism, Culture, Arts, Gaeltacht, Sport and Media (TCAGSM). The program provides a guaranteed, non-means-tested weekly payment of €325 to participating artists and creative workers. The initial pilot program, which ran from 2022 to 2025, involved 2,000 participants. Following the pilot’s success, the Irish government announced in October 2025 that the scheme would be made permanent and expanded.

3.2. Implementation and Timeline

The journey of the BIA from a pilot to a permanent program has been marked by several key milestones:

- 2022: The pilot scheme is launched, with an initial budget of €25 million.

- 2022-2025: The three-year pilot program is in operation, with ongoing research and data collection.

- September 2025: A cost-benefit analysis by Alma Economics is published, revealing significant positive impacts 1.

- October 2025: The results of a public consultation are released, showing overwhelming support for the scheme2.

- October 2025: The Irish government announces that the BIA will be made a permanent program as part of Budget 2026, with a new round of applications opening in September 20263.

3.3. Eligibility and Selection

Eligibility for the BIA pilot was designed to be broad, encompassing three main streams: practising artists, creative arts workers, and recent arts graduates. The definition of an artist from the Arts Act 2003 was used to determine eligibility. A key feature of the pilot was its selection process: participants were chosen from a pool of 8,200 eligible applicants through a randomised lottery. This approach was taken to ensure fairness and to create a robust basis for the research component of the program.

3.4. Research and Evaluation

A core component of the BIA pilot was its comprehensive research framework, designed to provide robust evidence for future policy decisions. This research had several key elements:

- Randomised Control Trial (RCT): The pilot was structured as an RCT, with a control group of 997 artists who did not receive the basic income payment but participated in the research surveys. This allowed for a rigorous comparison of outcomes between the two groups.

- Longitudinal Data Collection: Data was collected from both the participant and control groups at regular six-month intervals throughout the three-year pilot.

- External Evaluation: The government commissioned an independent cost-benefit analysis from Alma Economics to assess the economic and social returns of the program.

- Public Consultation: A wide-ranging public consultation was conducted to gauge public and stakeholder opinion on the future of the scheme.

4. Impact and Outcomes

The research and evaluation of the BIA pilot have revealed a wide range of positive impacts, spanning economic, social, and personal domains.

4.1. Economic Impact

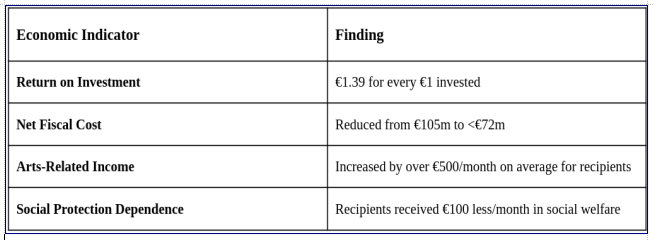

The cost-benefit analysis by Alma Economics demonstrated a strong positive economic return on the investment in the BIA. For every €1 of public money invested, the scheme generated €1.39 in return for society. The net fiscal cost of the pilot was also significantly lower than the headline figure, reduced from €105 million to under €72 million due to increased tax revenue and savings on social welfare payments.

4.2. Social and Personal Impact

The BIA has had a profound impact on the lives and well-being of the participating artists. The most significant social benefit identified in the economic analysis was the improvement in psychological well-being, valued at almost €80 million. Early findings from the research showed that BIA recipients experienced a nearly 10 percentage point decrease in depression and anxiety compared to the control group. Furthermore, recipients were 12 percentage points more likely to be able to support themselves through their arts work alone.

“The BIA payment is having a consistent, positive impact across almost all indicators – affecting practice development, sectoral retention, well-being, and deprivation.” – gov.ie

5. Political Context and Public Response

The successful implementation of the BIA scheme can be attributed to a confluence of political will and strong public support. The idea for the pilot emerged from the Arts and Culture Taskforce, which was established to address the challenges faced by the sector during the COVID-19 pandemic. The number one recommendation of the Taskforce’s “Life Worth Living Report” was to pilot a basic income scheme for artists.

The public response to the BIA has been overwhelmingly positive. A public consultation in 2025 received over 17,000 responses, with 97% of respondents supporting the permanent establishment of the scheme. This high level of public endorsement provided a strong mandate for the government to continue and expand the program.

6. International Context and Comparative Analysis

Ireland’s BIA scheme is a leading example of a growing international movement to provide guaranteed income for artists. Other jurisdictions have experimented with similar programs, most notably the Creatives Rebuild New York (CRNY) program in the United States. While both programs aim to provide financial stability for artists, there are some key differences in their design.

The Irish scheme is notable for its longer duration and its integration with a rigorous, government-led research program. This has positioned the BIA as a key case study for other countries considering similar policies.

7. Update: Terms of the Permanent Scheme (October 2025)

Following the announcement that the Basic Income for the Arts will be made permanent, further research has clarified the specific terms regarding the number of recipients and the duration of the payments.

7.1. Number of Artists

The permanent scheme will not be a continuation of payments for the original 2,000 pilot participants. Instead, it will be a new iteration:

- New Recipients: The scheme will open to 2,000 new artists and creative workers.

- Application Window: A new application window is scheduled to open in September 2026.

- Potential Expansion: There is a provision to expand the number of participants to 2,200 if additional funding is secured, with the government signaling its intention to incrementally increase capacity in future years.

The current pilot participants will stop receiving their payments when the pilot officially concludes in February 2026.

7.2. Duration of Payments: Not Indefinite

A critical clarification is the meaning of a “permanent” scheme. The research indicates that while the program itself is being established as a permanent fixture of Irish cultural policy, the payments to individual artists are not indefinite.

- Fixed Term: Like the pilot, the permanent scheme will provide payments to artists for a fixed term. The exact duration for the new cohort of artists has not yet been officially announced.

- Successor Scheme: Government officials have referred to the permanent program as a “successor scheme.” Minister for Culture Patrick O’Donovan stated, “The Basic Income for the Arts pilot scheme… will end in 2026, and I will bring a successor scheme to government with the intention of embedding a permanent basic income in the arts and culture sector.”4

- Gap in Payments: There will be a gap of up to six months between the end of the pilot in February 2026 and the commencement of payments for the new scheme in the latter half of 2026.

In summary, artists will be selected for the scheme and receive the basic income for a predetermined number of years, after which the payment will cease. The “permanent” nature of the scheme means the government is committed to running these fixed-term cycles of support for artists on an ongoing basis.

8. Conclusion

In conclusion, Ireland has indeed introduced a form of basic income for artists, and it has been a resounding success. The Basic Income for the Arts scheme has not only provided much-needed financial stability for artists but has also generated a positive return on investment for the Irish economy and society. The program’s transition from a pilot to a permanent fixture in the Irish cultural policy landscape marks a significant and progressive step in supporting the arts and creative sector. With its robust research framework and overwhelmingly positive results, Ireland’s BIA scheme serves as a powerful model for other countries seeking to foster a vibrant and sustainable creative economy.

9. References

- Basic Income for the Arts pilot produced over €100 million in Social and Economic Benefits ↩︎

- Survey finds strong support for Basic Income for the Arts ↩︎

- Basic income support scheme for artists to be made permanent and opened to new entrants in budget – The Irish Times ↩︎

- Government Commits to Permanent Basic Income for the Arts – Journal of Music ↩︎

– Ian Milliss

This article first appeared on Ian Milliss’ Substack feed https://substack.com/ @ianmilliss575982

Ian Milliss is an Australian artist, writer,

and cultural activist widely recognised as a pivotal figure in the development of conceptual art, political art, and inter-disciplinary practices in Australia since the late 1960s. Milliss is also a writer and historian of Australian art. His essays and public talks have been crucial in re-evaluating the history of conceptual and political art in Australia, often challenging established art historical narratives.

——————————————–